Nella maggior parte dei casi per la lavorazione vengono raccolti solo i germogli e/o le foglie giovani della pianta. Queste foglie giovani sono solitamente ricoperte da un’alta densità di peluria (tricomi). In generale sulle piante i peli sono sono presenti sui germogli, foglie e steli e presentano divere strutture e funzioni.

I peli sono il risultato dell’adattamento e dell’evoluzione della pianta per resistere a ad avversari e stress esterni. Nel loro ruolo di barriere fisiche, i tricomi svolgono nelle piante un ruolo protettivo nei confronti di insetti ed agenti patogeni microbici, consentono la riduzione della traspirazione e la perdita d’acqua nei periodi di siccità o con elevata temperatura e nello stesso tempo proteggono la foglia dal freddo eccessivo ed inoltre riflettono i raggi UV che risultano dannosi per la foglia. I peli nelle piante possono anche sintetizzare vari tipi di molecole, come, alcaloidi purinici, flavonoidi, e terpenoidi complessi che consentono alla pianta di avere una barriera chimica nei confronti di erbivori ed agenti patogeni.

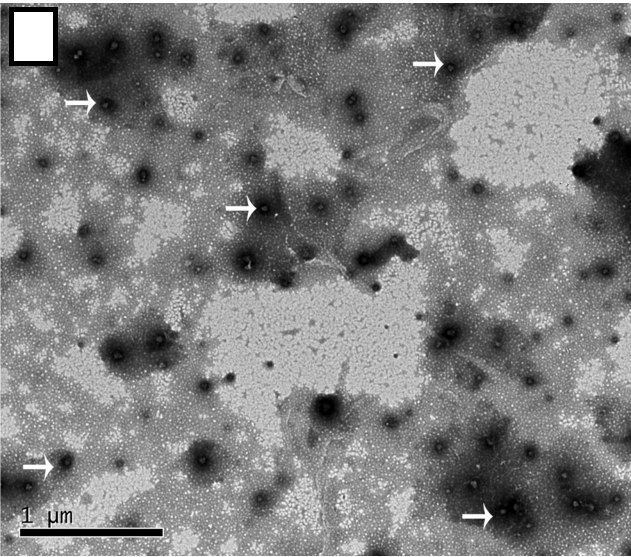

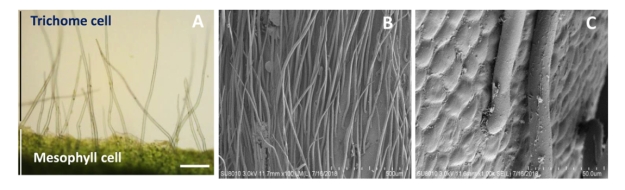

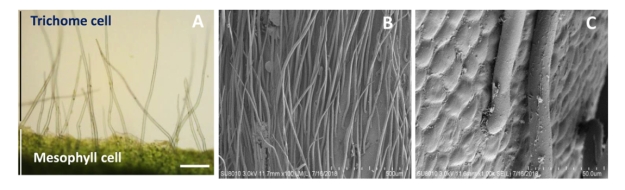

Tricomi del tè visti al microscopio. Li P. et al . Metabolite Profiling and Transcriptome Analysis Revealed the

Chemical Contributions of Tea Trichomes to Tea Flavors and Tea Plant Defenses. J. Agric. Food Chem 2020.

Anche nella pianta del tè i peli svolgono le funzioni sopra elencate. Da vari studi è emerso anche che nella peluria delle foglie di tè si accumulano tutta una serie di metaboliti come amminoacidi, catechine, sostanze volatili e caffeina che influiscono sul sapore dell’infuso. La quantità di queste molecole però è di molto inferiore a quella presente nelle foglie che perciò consevano sempre un ruolo prominente nelle qualità organolettiche dell’infuso finale.

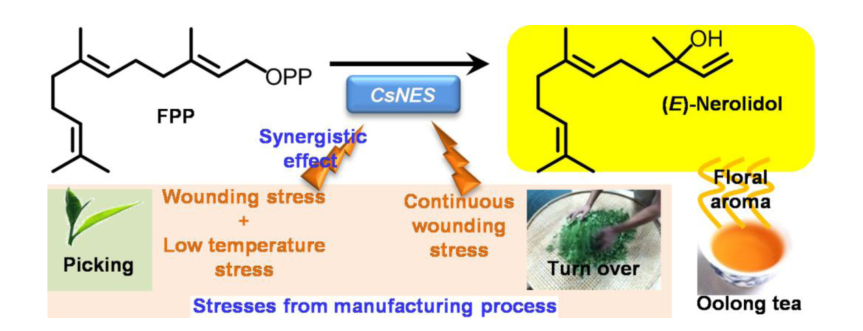

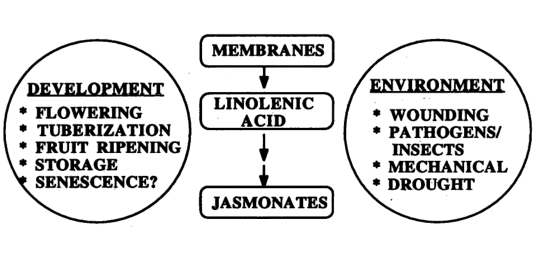

È importantissimo però mettere in rilievo il fatto che in diversi studi è stato determinato che la presenza di peluria sulla foglia consenta durante la lavorazione del tè, particolarmente in quello bianco, di incrementare tutta una serie di reazione di degradazione, come ad esempio quella dei lipidi riportata nell’immagine sottostante, e di portare quindi ad una maggiore presenza di molecole volatili contribuendo cosi indirettamente all’aroma del tè.

Le principali tappe biosintetiche portano alla formazione delle molecole molecole volatili dalla degradazione dei lipidi. (LOX = Lipossigenasi, HPL= Idroperossidoliasi, ADH= Alcoldeidrogenasi). Fonte: Tea aroma formation, Chi-Tang Ho et al., Food Science and Human Wellness 4 (2015) 9–27.

Bibliografia

Li J. et al. Evaluation of the contribution of trichomes to metabolite compositions of tea (Camellia sinensis) leaves and their products. LWT – Food Science and Technology 122 (2020) 109023

Cao H. et al. Integrative Transcriptomic and Metabolic Analyses Provide Insights into the Role of Trichomes in Tea Plant (Camellia Sinensis).Biomolecules 2020, 10, 311

Li P. et al . Metabolite Profiling and Transcriptome Analysis Revealed the

Chemical Contributions of Tea Trichomes to Tea Flavors and Tea

Plant Defenses. J. Agric. Food Chem 2020.

English Version

In most cases, only the shoots and/or young leaves of the plant are collected for processing. These young leaves are usually covered with a high density of hair (trichomes). In general, on plants the hairs are present on the shoots, leaves and stems and have different structures and functions.The hairs are the result of the adaptation and evolution of the plant to withstand adversaries and external stress. In their role as physical barriers, trichomes play a protective role in plants against insects and microbial pathogens, allow the reduction of transpiration and water loss in periods of drought or with high temperatures and at the same time protect the leaf from excessive cold and also reflect UV rays which are harmful to the leaf. Hair in plants can also synthesize various types of molecules, such as purine alkaloids, flavonoids, and complex terpenoids which allow the plant to have a chemical barrier against herbivores and pathogens.

Morphology of tea plant trichomes under a compound microscope (A) and a scanning electron microscope (B,C) . Li P. et al . Metabolite Profiling and Transcriptome Analysis Revealed the Chemical Contributions of Tea Trichomes to Tea Flavors and Tea Plant Defenses. J. Agric. Food Chem 2020.

In the tea plant, hair also performs the functions listed above. From various studies it has also emerged that a whole series of metabolites such as amino acids, catechins, volatile substances and caffeine accumulate in the tea leaves, which affect the flavor of the infusion. However, the quantity of these molecules is much lower than that present in the leaves which therefore always played a prominent role in the organoleptic qualities of the final infusion. However, it is very important to highlight the fact that in various studies it has been determined that the presence of hair on the leaf allows during the processing of tea, particularly in the white one, to increase a whole series of degradation reactions, such as that of lipids shown in the image below, and therefore lead to a greater presence of volatile molecules thus indirectly contributing to the aroma of the tea.

Bibliography

Li J. et al. Evaluation of the contribution of trichomes to metabolite compositions of tea (Camellia sinensis) leaves and their products. LWT – Food Science and Technology 122 (2020) 109023

Cao H. et al. Integrative Transcriptomic and Metabolic Analyses Provide Insights into the Role of Trichomes in Tea Plant (Camellia Sinensis).Biomolecules 2020, 10, 311

Li P. et al . Metabolite Profiling and Transcriptome Analysis Revealed the

Chemical Contributions of Tea Trichomes to Tea Flavors and Tea

Plant Defenses. J. Agric. Food Chem 2020.